Prospect of One-Income Future Means Delicate Financial Balancing Act for B.C. Woman

Andrew Allentuck

Situation:

Woman in early sixties has a large mortgage that will drain her retirement income, depends heavily on sharing living expenses with common-law partner

Solution:

Speak to an advisor about estate planning and insurance issues that would give her more security; cut spending to pay off mortgage quicker

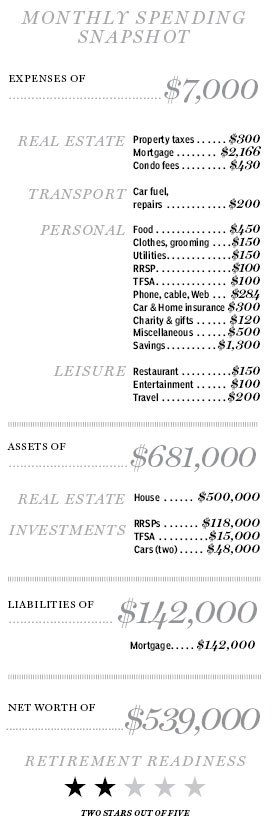

In a small town in B.C., a woman we’ll call Helena is 61 and approaching retirement. Her monthly cash flow, including $2,000 she gets from her significant other who shares her home, adds up to $7,000 a month. Gross income from her part-time work as a sales person in a local dress shop adds another $3,200. She receives a $1,300 pension from a former job and a $500 CPP Survivor Pension from her husband who died a dozen years ago from heart ailments. Her financial life is secure for now, but she worries that when she moves to full retirement, she will not be able to support herself.

The problem is both financial and personal. She has lived with a partner we’ll call Bill for five years. Bill, 72, chips in $2,000 toward household expenses out of his pension. But when he dies it dies as well since he has no survivor benefits on his company pension, set up before he met Helena.

So that pension, which with OAS and very modest CPP payments from a choppy job history, would leave nothing for Helena. His estate is very small and may be exhausted by the time he dies.

Without Bill’s monthly payments, Helena would barely break even and would have no margin for unplanned expenses. Her largest expense – actually a budget breaker if she were to lose both her salary and her partner’s supplement, is the $142,000 mortgage on her condo. She pays $2,166 a month on it.

“I love my home and hope to live in it for as long as possible,” she explains. “I realize, though, that if my boyfriend didn’t live here, I couldn’t afford it. I hope to pay off the mortgage in four years, at which time I would like to retire fully.”

Family Finance asked Derek Moran, head of Smarter Financial Planning Ltd. of Kelowna, B.C., to work with Helena. “I don’t think that the lady has an income problem,” he says. “She does, however, have a debt problem. If she can become mortgage-free, then ending her job and retiring is financially workable. She needs to look at interim solutions too before she retires. Insurance on her partner would help. Her priority is to keep her home, so that has to be the focus of this analysis.”

Debt Management

Helena actually has two mortgages, for she signed on to her daughter’s $83,500 mortgage. The daughter, in her 30s, makes the monthly $607 payments, but the risk of default remains Helena’s.

To become free of mortgage liability, Helena could apply to her daughter’s lender to be removed from that mortgage. Then the daughter, who now has secure employment herself, can improve her credit rating as she takes over the full responsibility for the mortgage.

Shedding her own mortgage, which still has $142,000 due, is going to take financial engineering, the planner says. Helena thinks she can do it in four years, but it will take six years with the present rate of payment.

If Helena uses her tax-free savings account, a total of $15,000, she can reduce the mortgage to $127,000. That will cut eight months off the mortgage and save $2,817 of interest over the life of the mortgage.

Helena has an antique car with an appraised value of $18,000. She does not drive it. She uses another car to get around. If she can get $18,000 for the antique car, she can pay the mortgage down to $109,000. At this point, with payments of $2,166 at present plus $100 she can add by stopping TFSA contributions, the mortgage will end a little short of her 65th birthday. To eliminate the mortgage completely by then, she would have to add another $200 a month to payments. She might reduce dining out, currently $150 a month, by $100, take $50 from the present $150 monthly clothing and grooming allowance, and $50 from the $100 each month she allocates to entertainment. They would be sacrifices, but only temporary ones.

Retirement Income

When fully retired, Helena will no longer have $3,200 a month from her work. At 65, she will lose her widow’s pension. She will add $826 from the Canada Pension Plan. She will have $1,326 a month from her defined benefit pension, $425 in Canadian dollars from a foreign pension for work done before she immigrated to Canada, $441 a month from Old Age Security based on 32 years of residence in Canada out of the 40 needed for full benefits, and $689 a month from her RRSP with the assumption that she adds $2,400 a year on top of her present $1,200 a year for four years at 3% real return and that the income is then paid out at the same rate for 25 years to her age 90. Her total monthly income would therefore be $3,707 before tax or $3,336 after 10% average tax. That would cover her present expenses month after her mortgage payments end and she stops $100 a month RRSP contributions.

The payments for cost sharing from her partner would then provide a cushion.

Helena will still have issues to face. If Bill were to pass away, she would not receive $2,000 a month from him. She would be eligible for additional funds from the Canada Pension Plan’s Allowance for the Survivor based on her late partner’s income and her own up to her 65th birthday. Her defined benefit pension, which will be about 35% of her pre-tax income after age 65, is not indexed. Nevertheless, her CPP, OAS and her former job pension are indexed. They will make up more than three-fourths of her total pre-tax retirement income.

Helena’s situation is a delicate balance. If her partner predeceases her, she could get a death benefit of up to $2,500 from CPP. But continuing income is a difficult situation. Her partner can address the problem by ensuring that he leaves her with some money in his will, but even that is uncertain, for he is a man of few means. One solution is to buy term life insurance with some of the money he gives to Helen each month. Reasonably healthy at 72, he could get $200,000 of coverage for 10 years for $2,254 to $3,881 a year – quotes vary among companies. If paid entirely to Helena, it would enable her to pay off her mortgage if she still has a balance at the time of his death and have some money leftover.

“With modest and temporary sacrifices, Helena can pay off her mortgage, retire debt-free and maintain her standard of living,” Mr. Moran says. “What is vital is that she think ahead and plan for the possibility that she would have mortgage expenses if he were to die before the mortgage is paid off. Discussion of these problems with a financial planner, accountant or lawyer would be very helpful. That they have not done this yet indicates, in a sense, how urgent it is that they do it.”

(C) The Financial Post, Used By Permission